You are here

Critical Minerals for Energy Transition: Linchpin or Risk?

Overview

As the world races towards a net-zero future, the critical mineral value chain emerges as both a linchpin and a potential obstacle to achieving climate neutrality goals. While countries have been adopting a range of initiatives to secure supply of critical minerals required for transition, the environmental, social and economic implications of an unsustainable value chain are often ignored in the policy debates. Ensuring the sustainability of this value chain is crucial, given its pivotal role in supplying the minerals essential for clean energy technologies. However, without adequate policies and governance mechanisms, the critical mineral sector could pose significant risks to environment sustainability, social equity, and economic stability and can eventually lead to risks to energy transition goals.

Risks of Critical Mineral Value Chain

The global push towards decarbonisation will lead to significant demand for critical minerals to support its transition. The demand for certain critical minerals is projected to grow up to 500 per cent by 2050,1 with sectors such as transportation, energy, and semiconductor manufacturing driving this growth. Importing countries face economic risks due to potential supply shortages and geopolitical tensions. In view of this surging demand, many importing countries have been shaping strategies to ensure the uninterrupted supplies of minerals critical to fuel their climate mitigation initiatives. About 30 to 50 minerals have been listed as critical to energy transition or strategic to national security, by many major economies.

While Canada, Australia and many European countries are major producers of some minerals, a significant share of critical minerals pivotal for energy clean technologies are sourced from many developing and least developed economies, which are rich in biodiversity and have fragile systems. The overlap of mining locations and areas rich in biodiversity threatens serval species of flora and fauna.2 For example, studies note that one-third of Africa’s great ape population faces mining-related risks,3 while several migratory fish species and river-dwelling birds are affected by mining related water pollution in Brazil.4

Critical mineral mining related adverse impacts are not limited to the biodiversity in one or two regions, but happens on a global scale mostly due to the increasing land usage and the corresponding impact on water resources, land and air.5 Weak governance mechanisms and not so stringent environmental regulations in these developing economies help the mining and processing industry to flourish. The fact that the industry contributes to economic and social benefits in terms of resource rent and employment opportunities, also justifies less stringent regulations by the government.6 However, the larger adverse impact on the environment, people and society – mostly related to the mining, processing, and waste management activities, are often not paid adequate attention in policy making.

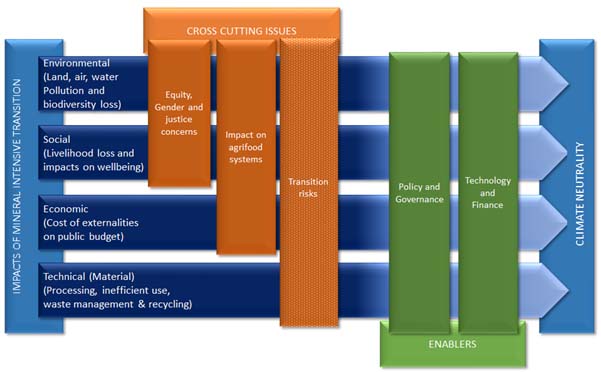

Key challenges and crosscutting issues in the value chain demand efficient policy, governance, technology and financial measures to enable just and equitable transition to climate neutrality

Source: Authors

The environmental impacts include biodiversity loss, land degradation, water resource depletion and pollution stemming from the extraction and processing. Social implications range from disruptions to local communities and livelihoods to altering employment scenarios in mining regions. Economic challenges are particularly acute for producing countries, where the ripple effects of environmental and social impacts can have far-reaching consequences on national economy. Technical challenges within the value chain include inefficient processing, usage, and limited recycling of critical minerals, exacerbating resource inefficiencies and environmental degradation. In addition to these core challenges, cross-cutting issues such as equity, gender and justice concerns, impact on agrifood systems, and transition risks for businesses further complicate the landscape.

While part of the world is accelerating towards clean energy future, many poor economies will eventually end up damaging their environment This raises the question how well is the world prepared to steer towards a just and equitable transition to net-zero future.

To address these challenges, robust policies and governance mechanisms are essential. Stakeholders across the globe must collaborate to establish transparent regulatory frameworks, promote responsible mining practices, and enforce environmental and social standards throughout the value chain. Additionally, financial support and technological innovations are crucial for enhancing the sustainability and efficiency of critical mineral production and utilisation.

What Can the World do for Risk Alleviation?

To alleviate these risks and ensure a smooth transition, three specific efforts must be made, in addition to the conventional approaches. First, while supply challenges and geopolitical tensions are significant concerns in the critical mineral value chain, focusing solely on these aspects overlooks the broader spectrum of risks. Stakeholders will need to expand the scope of planning beyond traditional supply-centric perspectives, to develop strategies that address the multifaceted risks of the value chain. A starting point could be to shape and implement stringent regulations to ensure responsible mining practices, improving transparency in the value chain, and investing in technologies that enhances efficient processing of minerals. Stakeholders will also need to ensure equitable distribution of benefits to the local and indigenous population whose livelihood may be affected due to the mining impacts.

Secondly, many of the mining activities lead to innumerable impact on biodiversity and natural resources. While sustainable practices are essential, aiming for regenerative approaches can yield even greater benefits. Regenerative strategies that seek to restore ecosystems, protect biodiversity, and ensure well-being of the local communities are essential. Regenerative outcome is also closely linked to how efficiently stakeholders are adopting circular economic principles. Designing processes with end-of-life recycling stakeholders can manage waste and maximise resource efficiency in key operations in mining and processing.

Lastly, responsible transition is utmost important. The race to climate neutrality must be guided by responsible practices and environmental stewardship is paramount. The businesses will also need to embrace responsible transition initiatives and engage in meaningful dialogue with local communities. However, it is important to make these interventions transformational unlike the current landscape where environmental, social and governance (ESG) norms are often criticised for being limited to mere target meeting exercise.7

Conclusion

Addressing the challenges of the critical mineral value chain requires a concerted effort from governments, industry players, civil society and local communities. By implementing robust policies, fostering transparency and accountability, investing in technological innovation, and prioritising social equity, countries can navigate the complexities of the energy transition while minimising environmental impacts and promoting inclusive development. By looking beyond supply challenges and geopolitics, embracing sustainable and regenerative practices, and transitioning responsibly, the world can foster a resilient and equitable transition to a sustainable energy future.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. “Climate-Smart Mining: Minerals for Climate Action”, The World Bank, 26 May 2019.

- 2. “Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transition”, IEA, 2021.

- 3. “Threat of Mining to African Great Apes”, ScienceAdvances, Vol 10, No. 4, 2024.

- 4. “Mining Activity in Brazil and Negligence in Action”, Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation, Volume 18, Issue 2, April–June 2020, pp. 139-144.

- 5. “An Update on Global Mining Land Use”, Scientific Data, Article Number 433 (2022).

- 6. “Environmental Aspects of Critical Minerals in Africa in the Clean Energy Transition”, Proceedings of African Ministerial Conference on the Environment, 13 July 2023.

- 7. Talman, K. “How 'ESG' Came to Mean Everything and Nothing”, BBC, 15 November 2023.