ECOWAS Leadership Transition: Between Symbolism and Substance

- July 28, 2025 |

- IDSA Comments

Divergent governance models and shifting external alignments define the broader regional landscape. While the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), a regional bloc formed by Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso, has turned towards nationalist, military-led rule, others remain committed to democratic norms and multilateralism. This divergence has opened space for non-Western powers such as Russia, China and the Gulf states to expand their influence, while traditional Western actors reassess their engagement. These shifts have undermined the collective vision of integration that once defined West Africa, placing regional mechanisms under severe stress.

President Bio’s Chairmanship of ECOWAS is in the backdrop of an acute regional crisis. The withdrawal of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger has significantly undermined ECOWAS’s cohesion.[2] Compounding this challenge, Sierra Leone and Guinea are embroiled in a renewed territorial dispute. At the same time, the broader region faces an intensifying terrorism threat, with attacks spreading from the Sahel into previously stable coastal states such as Benin and Togo.[3] As a former military officer who transitioned into an elected leader, Bio represents continuity and change. His leadership will be crucial in determining whether ECOWAS can restore its credibility and unity or continue to fragment under the strain of internal discord and mounting geopolitical pressures.

The choice of Julius Bio as ECOWAS Chair is, on the surface, a nod to the bloc’s founding ethos. His dual identity as a former ECOMOG soldier and elected leader offers an appealing transformation narrative, from civil war and coups towards democratic normalisation. His chairmanship marks Sierra Leone’s return to ECOWAS leadership after more than four decades, offering a symbolic gesture towards regional inclusivity.

Yet symbolism can only go so far. Bio’s democratic legitimacy remains controversial. Allegations of voter suppression, non-transparency and violence marred his 2023 re-election. International observers expressed concern, while domestic critics highlighted state repression and a troubling rise in reports of extrajudicial killings. Reports estimate over 200 such cases.[4] Moreover, Sierra Leone’s alleged sheltering of a notorious European drug trafficker has tarnished its credibility in European diplomatic circles and underscored West Africa’s vulnerabilities to transnational criminal networks.[5] These concerns risk undermining ECOWAS’s moral authority just as it seeks to reaffirm its normative framework.

Notwithstanding these domestic troubles, Bio has positioned himself as a potential bridge-builder. In August 2024, he travelled to Burkina Faso to meet Captain Ibrahim Traoré, demonstrating a willingness to engage across the regional divide. His trajectory, from junta leader to elected president, might appeal to Sahelian counterparts facing their legitimacy dilemmas. However, tangible impacts remain unclear, and whether such outreach can lead to meaningful reconciliation remains uncertain.

President Bio outlined four principal priorities in his inaugural address as Chair of ECOWAS: restoring constitutional order and deepening democracy; revitalising regional security cooperation; unlocking economic integration; and building institutional credibility. Yet, these pledges must be substantiated through tangible action. The organisation’s credibility now hinges on its capacity to convert these commitments into meaningful and sustained reforms.

Bio’s pledges framed expectations for reform, yet the communiqué revealed a cautious and limited approach to implementation. The final communiqué projected resolve but revealed ECOWAS’s constrained position. It intends to appoint a Chief Negotiator to manage the AES withdrawal and preserve regional integration, while calling for faster activation of the Standby Force through coordinated funding. Though timelines for Guinea’s transition and elections in Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea-Bissau were noted, the document largely reflected a reactive stance.[6] Rather than signalling renewal, it underscored the growing gap between ECOWAS’s ambitions and diminishing capacity. The limits revealed in the communiqué are symptomatic of a wider erosion of ECOWAS’s supranational credibility.

The institutional limits of ECOWAS have also become glaringly apparent. Chief among these is the erosion of its legal authority. Nigeria’s repeated failure to comply with ECOWAS Community Court of Justice rulings has raised serious concerns. As the bloc’s most powerful member, Nigeria’s disregard for the court’s judgements sends a damaging signal to other states and weakens the bloc’s supranational credibility. Although the ECOWAS Treaty legally binds members to comply, enforcement mechanisms are absent. National courts often override regional directives, citing constitutional supremacy, and political leaders show little will to prioritise regional obligations over domestic convenience.[7]

Operational deficiencies match this legal vacuum in ECOWAS’s security architecture. The ECOWAS Standby Force, though envisioned as a rapid-response mechanism, remains nominal mainly. Despite a US$ 2.6 billion revitalisation plan,[8] the force suffers from chronic underfunding, inadequate coordination and political hesitancy. Nigeria, the traditional backbone of ECOWAS military operations, now faces severe internal security crises that have undercut its capacity to project influence across the region. Reflecting this concern, the outgoing Chair underscored the slow-paced activation of the Standby Force, implicitly acknowledging that Nigeria cannot shoulder the burden alone and must secure financial contributions and political commitment from other member states.[9]

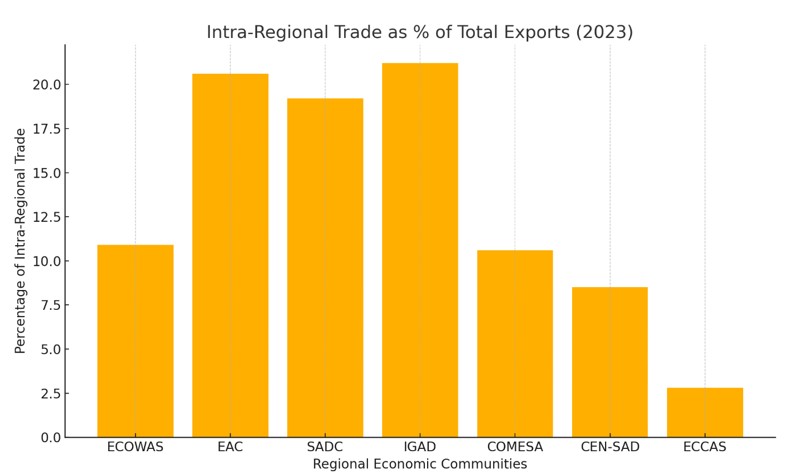

Economically, the region is stagnating. Intra-ECOWAS trade remains limited and structurally weak, accounting for only 10.9 per cent of the bloc’s total exports in 2023. This figure is significantly lower than that of other African regional economic communities: the East African Community (EAC) records about 20.6 per cent, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) around 19.2 per cent, and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) approximately 21.2 per cent.[10]

Source: Prepared by the author based on the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa report.

Despite the Common External Tariff (CET), implementation is uneven, with member states frequently invoking exceptions or surcharges for uniformity. The bloc suffers from a proliferation of non-tariff barriers (NTBs), including customs inefficiencies, inconsistent classification of goods and road checkpoints that drive up costs and discourage cross-border commerce.

Overlapping memberships, most notably between ECOWAS and the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU), create conflicting obligations and dilute the political focus required for deeper integration. These structural flaws have also hindered flagship initiatives, most visibly the long-delayed ECO currency project. The stalled ECO currency project underscores ECOWAS’s wider dysfunction. Persistent instability, economic disparities and weak infrastructure continue to block progress, and without structural reforms, the currency risks remaining a symbolic aspiration rather than a transformative tool for regional integration.

Moreover, the AES’s recent decision to impose a 0.5 per cent levy on goods from ECOWAS states reveals a deeper unravelling.[11] This is not merely a trade policy but a declaration of disengagement. The AES’s growing ties with external actors like Russia and their rejection of ECOWAS principles suggest that West Africa no longer operates within a single political or economic framework.

Despite this, Tinubu’s attempts at reconciliation through diplomacy, sanctions relief and mediation failed as AES states deepened their split, formalised during their 2024 summit. Acknowledging ECOWAS’s limitations, Tinubu hinted at a more pragmatic and inclusive approach, yet no concrete strategic shift followed. Meanwhile, emerging leaders such as Ghana’s John Mahama and Senegal’s Bassirou Diomaye Faye have called for dialogue over isolation, but these appeals lack weight without meaningful institutional renewal.[12]

Conclusion

The outlook is not entirely pessimistic despite the significant challenges confronting ECOWAS, including persistent intra-regional trade deficits, political instability and institutional inefficiencies. The community’s achievements in operationalising free movement of persons, harmonising external tariffs and establishing internally funded initiatives underscore its potential as a viable platform for regional cooperation. These accomplishments provide a foundation upon which future reforms can be anchored. The current leadership transition offers a critical juncture to recalibrate priorities, address structural weaknesses, and translate normative frameworks into measurable outcomes. With sustained political will and coordinated policy implementation, ECOWAS can reassert its role as a central driver of West Africa’s economic integration and political stability.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

[1] “Final Communique of the 67th Ordinary Session of the Authority of Heads of State and Government”, ECOWAS CEDEAO, 22 June 2025.

[2] Chinedu Asadu, “ECOWAS Pledges to ‘Keep Door Open’ After 3 Coup-hit West African Nations Exit Regional Bloc”, Associated Press, 29 January 2025.

[3] “West Africa and the Sahel”, Security Council Report, 31 March 2025.

[4] Abdul Rashid Thomas, “Sierra Leone’s President Bio Takes Over ECOWAS Chairmanship, Sparking Questions”, Sierra Leone Telegraph, 23 June 2025.

[5] Damien Glez, “How Sierra Leone’s First Lady Exposed a Dutch Drug Trafficker”, The Africa Report, 15 February 2025.

[6] “Final Communique of the 67th Ordinary Session of the Authority of Heads of State and Government”, no. 1.

[7] Solomon Odeniyi, “Concerns Over Relevance of ECOWAS Court as Member Nations Disregard Judgments”, PUNCH, 23 December 2024.

[8] Ope Adetayo, “West Africa’s ECOWAS Bloc Needs up to $2.6 billion a year for Security Force”, Reuters, 27 June 2024.

[9] “Tinubu: ‘I am Concerned About the Slow Pace of ECOWAS Standby Force’”, The State House, Abuja, 22 June 2025.

[10] “Assessing Regional Integration in Africa ARIA XI”, United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, 12 July 2025.

[11] “West African Juntas Impose Levy on Imported Goods”, Reuters, 30 March 2025.

[12] Eniola Akinkuotu, “Will Senegal’s Faye or Ghana’s Mahama Succeed Tinubu at ECOWAS?”, The Africa Report, 16 June 2025.