You are here

The New Government in Iraq: Challenges Ahead

Summary: In 2019, disillusioned with their political system, thousands of Iraqis protested and called for an end to rampant corruption siphoning their country's oil wealth, for better public services and change in the government. The protest triggered a new election in October 2021, the result of which has given a new picture, unlike in the past. The Iraqi nationalist parties have emerged as the main gainers. This has generated hope that the new government will try to address the issues of political instability, economic crisis, inflation, unemployment, among others. The government will also have to maintain a balance between the US, the Arab allies, Iran and Turkey, the main external actors active in Iraq. Given the number and intensity of the challenges, the new government will have to show some extraordinary diplomatic skills to manage them.

Summary: In 2019, disillusioned with their political system, thousands of Iraqis protested and called for an end to rampant corruption siphoning their country's oil wealth, for better public services and change in the government. The protest triggered a new election in October 2021, the result of which has given a new picture, unlike in the past. The Iraqi nationalist parties have emerged as the main gainers. This has generated hope that the new government will try to address the issues of political instability, economic crisis, inflation, unemployment, among others. The government will also have to maintain a balance between the US, the Arab allies, Iran and Turkey, the main external actors active in Iraq. Given the number and intensity of the challenges, the new government will have to show some extraordinary diplomatic skills to manage them.

Since the fall of the Saddam regime in 2003, political stability in Iraq has been marred by ethnic strife, insurgencies and frequent violent conflicts. In such a chaotic environment, efforts to restore legitimacy and development of the country have proved to be ineffective. Due to weak state institutions and their lack of authority to impose decision in the country, even basic governance has been a challenge. For example, the government could not bring stability in areas previously controlled by the Islamic groups. Kirkuk does not have a governor till date. The rise in corruption is another concern being raised by the common people as it is affecting them the most. A recent study by Enabling Peace in Iraq Centre shows that about 80 per cent of Iraqis view corruption as one of the biggest problems faced by Iraq. This is nearly 10 times more than the number of people who mention the Islamic State (8.8 per cent) or healthcare/Covid-19 (5.9 per cent) as more serious issues.1

The people of Iraq have been protesting against the abysmal conditions in the country to force the government to provide better governance, security and other services. The Sadr protests of 2016 and the Basra protests of 2018 were aimed at asking the government to deliver on these aspects. One of the prominent protests was the October revolution in 2019,2

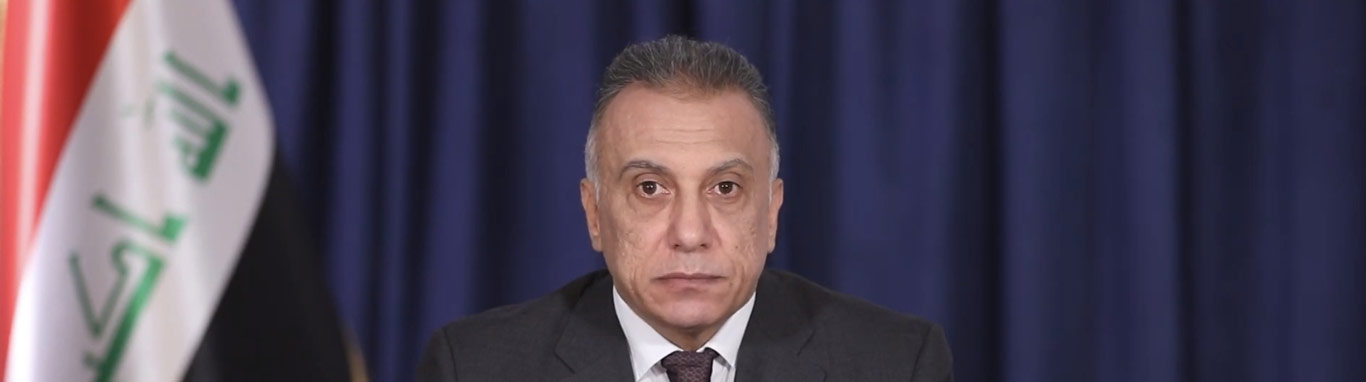

The growing unrest in the country forced President Barham Salih to appoint an outsider Mustafa Al-Kadhimi as the Prime Minister, who managed to conduct the parliamentary election in Iraq in October 2021.3 The outcome of the election has weakened pro-Iranian groups, as it gave out a clear message that the Iraqis don’t want Tehran’s interference in Iraq’s internal affairs.4 The newly introduced electoral law made it easier for smaller parties and independent candidates to canvas in smaller constituency with minimum budget. The new law changes each of the Iraq’s 18 provinces into several electoral districts and allocate one parliamentary seat per 1,00,000 people. The law also prevents the traditional parties from running on unified lists, which in past helped them to retain their seats and political powers. Instead, the seats would go to whoever gets most of the votes in the electoral districts.5

October 2021 Election Results

On 10 October 2021, Iraq voted to elect 329 new parliamentarians who will choose the next prime minster.6 As predicted, Muqtada al-Sadr’s party—the Sadrist Movement—emerged as the big winner, securing at least 73 seats. The Popular Mobilisation Front (PMU) affiliated political blocs including the Fateh party secured 20 seats.7 Five of these seats are for Hadi al-Amiri’s Badr Organisation; 10 for Qais Khazali’s Asaib Ahl al-Haq and five are for smaller blocs such as Sanad al-Watani. In 2018 election, Fateh alone was the second largest party with 48 seats in the parliament.8 The drop in seats is a setback for Iran as PMU and Fateh are considered the most reliable pro-Iranian groups in Baghdad.

Another Iran-backed group—Kataib Hezbollah or Hezbollah Brigades—also entered Iraqi politics by forming its own political bloc called the Huqooq Movement under the leadership of Hussein Muanis.9 The group secured one seat. The loss of the pro-Iran parties was a message that Iraqis are not willing to tolerate proxy groups that undermine the government.10

Surprisingly, former Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki’s party, State of Law Coalition benefitted from anti-Iranian sentiments among the Iraqis. The party secured 37 seats, despite facing strong opposition from the local, regional and international parties which blamed Maliki for Iraq losing about a third of its land to the IS group.11 In 2018 election, his party had secured 25 seats.

Showing some signs of overcoming the divisions among Iraqi Sunni political factions, the Sunnis have emerged as a more cohesive political force this time. Progress Party or the Taqadom Party, an umbrella body for several Sunni parties, headed by current parliament speaker Mohammed al-Halbousi won 37 seats, making it the second largest in parliament. Azem Iraq Alliance, another major Sunni group, headed by businessman Khamis al-Khanjar won 12 seats. The alliance includes eight parties and prominent Sunni figures such as former speakers Mahmoud al-Mashhadani and Salim al-Jubouri, and some former ministers and lawmakers.

The Kurdish parties won 61 seats. The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), headed by Masoud Barzani, which dominates the government of the autonomous Kurdish region of Iraq secured 32 seats and its rival, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) party headed by the former Iraqi President Jalal Talabani won 15 seats.

Lastly, the implementation of new electoral law allowed new hopefuls such as tribal leaders, business people and civil society activists to join the political race and challenge the traditional political parties. The two such new political blocs which managed to secure nine seats each are the New Generation and the new Imtidad Movement, which promised to tackle corruption. They are likely to become part of the winning political blocs, rather than forming coalition of their own. However, they could still act as a watchdog for the government to effectively function.

Possible Coalition

The 2021 parliamentary election suggests that Sadrists have gained popularity while Fateh’s support has declined. However, Fateh still maintains powerful coercive capital and is likely to play a major role in the formation of the new government. In fact, a coalition between Fateh and PUK is expected.12 PUK has recently announced its support for President Barham Salih, arguably the candidate with the most political leverage in Iraq.13 Another possible coalition that is likely to emerge is between Fateh and State of Law Coalition. Maliki is eyeing on the premiership, however, without the backing of Fateh, he may not be able to fulfil his political aspirations. On the other side, Iraqi armed groups do not want Maliki as their prime minister, but they do see him as an important ally after the election.14

The most interesting change could be Sunni and Kurdish parties aligning with Fateh’s main rival—Sadrist Movement—to form the next government. Sadrist Movement is expected to form coalition with Kurdistan Democratic Party and Progress Party. All three parties have secured majority votes in the elections. In other words, they will play a major role in electing the prime minister and the speaker of the parliament. It is already estimated that Progress Party leader Halbousi is well-placed to return as a speaker.15 Also, Sadr has nominated four names for the Iraqi premiership—Mustafa Al-Khadhimi, Iraq’s ambassador to the UK, Jaafar al-Sadr, Deputy Parliament speaker, Hasan al-Kaabi and the Sadrist leader Nassar al-Rubai.16

Among the prime ministerial candidates, Kadhimi has better chances to retain his premiership, as he is not associated with any political party and is not driven by any political ideology. Thus, he may not face much resentment from the nationalists. More importantly, during his one-year premiership, Kadhimi has performed moderately well when compared to others. On the economic front, Kadhimi introduced the “White Paper for Economic Reforms” in November 2020 which mentioned potential ideas to recover Iraqi economy.17 However, given the nature of Iraq’s economic crisis, it would be unrealistic to expect any government reforms to yield positive results in just a year or two. Also, economic development doesn’t necessarily end the institutionalised corruption. On the political front, Kadhimi had launched an anti-corruption campaign.18 Regionally, he has also emerged as a significant figure for foreign actors like the US, Iran and Saudi Arabia which see him as an acceptable leader for a complicated country.19

Challenges

Despite the smooth process of the Prime Minister nominations, a number of future challenges lie in wait for the formation of a new government at both domestic and regional fronts.

Domestic Challenges

The next government is likely to face formidable challenges in introducing short-term as well as long-term economic reforms, fighting corruption, improving basic services and addressing unemployment, inflation and poverty in Iraq. The government will also have to deal with problems accumulated over the years that forced Mahdi to resign as well as the crisis that emerged thereafter, especially prosecuting killers of protesters who revolted against the government in 2019.20 The country is also plagued with health and public crisis as a result of worldwide Covid-19 outbreak. Iraq has the lowest vaccination rate in the region. Till date, about one million people have been fully vaccinated, representing less than 2 per cent of the population.21

The government will also have to be very careful in allotting oil-rich states to political parties. Baghdad draws 94 per cent of its budget from the revenue generated from oil.22 The 2021 Iraqi budget was US$ 89 billion, with an estimated deficit of US$ 19 billion which was calculated on the basis of its oil-selling price of US$ 45 per barrel.23 The challenge is to use this revenue to improve lives of Iraqis, rather than coming under pressure and dividing it within the networks of ruling political parties.

Another challenge would be the reconstruction of the country. From 2003 to 2014, more than US$ 220 billion were spent on rebuilding the country. In the post-ISIS period, Iraq held a reconstruction conference in Kuwait where key international donors pledged US$ 30 billion. Till date, many of the promised funds have not been transferred due to the corruption and mismanagement of funds by the previous government.24 Without greater accountability and transparency in the government, it would be extremely difficult to break the cycle of corruption and inefficiency and gain trust of the donors.

Besides, security challenges represent a vital concern since militias affiliated to ISIS continue to carry out sporadic attacks across the country, leading to a number of casualties and financial losses.25 As compared to the 2014 ISIS uprising, the terrorist groups are down to 5 per cent. However, experts state that capturing or killing small groups is much more difficult than killing militants in open battles. Surgical counter-terrorism raids will need to be undertaken for at least 5–10 years to eliminate the remaining terrorists.26 Counter-terrorism operations would also mean that the new government will have to collaborate with Iran-backed PMU, which was established to help Iraq defeat the ISIS in 2014.

Regional Challenges

Since the 2003 US-led invasion, every government in Iraq has needed a go-ahead from Tehran and Washington. For instance, in 2018, Iran and the US compromised on the appointment of Al-Kadhimi as the prime minister. It is crucial for the new government to maintain good relations with Iran as well the US for two reasons. First, for negotiating the Status of Force Agreement (SOFA) with the US, to remove its combat troops from Iraq by end of 2021.27 Second, to continue signaling to the new Raisi Ebrahim government that Iraq wants strong ties with Iran based on the “principle of non-interference in the internal affairs” of the country.28 It would also build trust among Iraqi population who demanded removal of foreign influence in the country in October 2019 protest. However, it is not going to be easy for the new government.

While the demand of US withdrawal is strongest among the PMU, especially after the January 2020 US drone strike that killed General Qassem Soleimani, head of Iran’s expeditionary Quds force, and PMU Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, it is resisted by others, especially the Kurdish parties.29 Also, there is a growing demand from the Kurds30 and Sunnis for normalising relations with the US’ closet ally, Israel—another unwelcome development to Iran and its affiliate groups in Iraq.31

Along with the Kurds, the Gulf countries that remain deeply concerned about Iranian influence in the region, will certainly look for ways to make sure the new government stays close to the US and its allies.32 In fact, the two dominant Gulf powers Saudi Arabia and UAE view Israel as a formidable partner that is willing to act forcibly to counter its regional adversary—Iran.

While Russia, along with Iran views Iraq as another theatre in which it can work to end the US-led world order and re-establish itself as a dominant power, but in doing so damages Iraqi stability. Russia exploits and exacerbates tensions in the US–Iraqi ties to accelerate the US withdrawal from the region. Kremlin’s increasing ties with Iran’s proxy militia network in Iraq could threaten not only Iraqi stability but also US forces and interests in Iraq and Syria.

Another challenge for Baghdad is to deal with Turkey which is increasingly disregarding Iraqi stability. In 2018, Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan launched a formal operation against the Kurds in Iraq.33 The Baghdad administration as well as the Iran-backed paramilitary groups condemned Turkish attack as an infringement upon its country’s sovereignty. Iraq has also filed a formal complaint against Turkey.34 On the other side, Erdogan claims that it is an act of self-defense since Iraqi government failed to prevent its land being used as a base to attack Turkish border.35

With the October 2021 election, Ankara is looking for a new government in Baghdad with which it can coordinate and in particular, not block Turkish soldiers from carrying out continuous attacks on PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) and its hideouts on the northern border. However, given the majority of seats Kurdish parties secured in the 2021 election, it is clear that they will not only play a major role in the formation of government but will also influence Iraq’s regional policies. The new government will have to be very careful in negotiating these issues, keeping the interests of the state, political parties and the people into consideration. Any miscalculation could lead to the downfall of the government.

Conclusion

Since the fall of the Saddam regime in 2003, Iraq has not been able to gain political stability or made any economic progress. The removal of the Saddam regime exposed the ethnic fault-lines within the country and various ethnic groups started fighting to gain power and exercise it to their own benefit. Since the Shi’ite constitute the majority of Iraqi population, they were able to gain the most powerful posts due to the electoral political calculations. However, their ways of undermining the interests of other groups have only deteriorated the political crisis further. The gulf between the various ethnic groups has also led to rampant corruption and poor governance. Also, increasing disentitlement of the Sunnis led to the rise of ISIS.

However, holding the elections and formation of governments in Iraq has generated hope, especially since corrupt politicians and leaders were forced to resign by mass protests. The latest election was also an outcome of such protests. The result of the elections had given a new picture, unlike in the past. The Iraqi nationalist parties have emerged as the main gainers. This has generated hope that the new government will try to address the issues of political instability, economic crisis, inflation, unemployment, among others. The government will also have to maintain a balance between the US, the Arab allies and Iran, the main external actors active in Iraq. Given the number and intensity of the challenges, the new government will have to show some extraordinary diplomatic skills to manage them.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. “Inside Look at Iraq's Popular Movement For Reform”, Enabling Peace in Iraq Center, October 2021.

- 2. “Chronology of Events—Iraq”, Security Council Report, 6 October 2020.

also known as the Tishreen Movement, during which Iraqis demanded to end the Muhasasa system—an ethno-sectarian power sharing arrangement that has reinforced Iraq’s corrupt political system since 2003. Other demands of the movement were changes in the electoral law and early elections to create a government of technocrats. “Iraq: The Protest Movement and Treatment of Protesters and Activists”, Country of Origin Information Report, European Asylum Support Office, October 2020. Iraqis’ uproar forced the then Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi to step down. However, his resignation resulted in months of political deadlock as the major political parties were unable to pick Mahdi’s replacement. Since the removal of Saddam Hussein, Iraq’s prime ministerial candidate has been from the Shi’ite Dawa Party. So far, the Shia leaders have been unable to share power with the Sunnis or the Kurdish in a stable way. They fear that the Kurds would want independence and the Sunnis would try to regain their old dominance. On the other side, Sunni blocs are reluctant to accept Shi’ite in power.

“Islamist Politics in Iraq after Saddam Hussein”, Special Report 108, United States Institute of Peace, August 2003. - 3. “Iraq’s Head of Intelligence Named Third PM-designate This Year”, Al Jazeera, 9 April 2020.

- 4. “Iraq’s Head of Intelligence Named Third PM-designate This Year”, Al Jazeera, 9 April 2020.

- 5. “Iraq: Prime Minister Announces Early Parliamentary Elections and Urges Implementation of New Election Law”, Library of Congress, 14 August 2020.

- 6. “Iraq Elections: October 2021”, United Nations–Iraq, October 2021.

- 7. Ali Jawad, “Iraq Announces Full Results of Parliamentary Elections”, Anadolu Agency, 17 October 2021.

- 8. Nagapushpa Devendra, “Iraq Post-Elections: Government Formation amid Vote Recount”, MP-IDSA–West Asia Watch, Vol. 1, No. 3, May–June 2018.

- 9. Kaitaib Hezbollah is on the US list of terrorist organisations and is accused of targeting American forces in Iraq. Muanis himself was jailed by the Americans for four years from 2008 to 2012 for fighting against US troops.

- 10. “Treasury Sanctions Iran-Backed Militia Leaders Who Killed Innocent Demonstrators in Iraq”, US Department of Treasury, 6 December 2019. And “Iraq: State Appears Complicit in Massacre of Protesters”, Human Rights Watch, 16 December 2019.

- 11. Mohamad Bazzi, “It’s Time for Iraq’s Nuri al-Maliki to Go”, Quartz, 20 June 2014.

- 12. “Kurdistan’s PUK Forges Alliance with Pro-Iran Factions in Iraq Ahead of Election”, The Arab Weekly, 8 June 2021.

- 13. “Iraqi President Seeks Second Term, Believes He Has More to Offer”, The Arab Weekly, 20 September 2021.

- 14. “MEE: Nouri al-Maliki is Plotting His Comeback in the Upcoming Elections”, Shafaq News, 14 August 2021.

- 15. Andrew Parasiliti, Elizabeth Hagedorn and Joe Snell, “The Takeaway: Sunni ‘Awakening’ is a Big Story from Iraq’s Elections”, Al-Monitor, 13 October 2021.

- 16. “Including al-Kadhimi, al-Sadr Proposes Four Names for the Prime Ministry”, Shafaq News, 6 October 2021.

- 17. “What is the White Paper for Economic Reform?”, Government of Iraq, 26 November 2020.

- 18. “Iraq PM Launches Campaign Against Customs Corruption, Vows Reforms”, The Arab Weekly, 12 July 2020.

- 19. Paul Iddon, “Can Iraq's Prime Minister Win Re-election and Curb the Power of Iran-backed Militias?”, Middle East Eye, 1 October 2021.

- 20. Ibid.

- 21. “COVID-19 Vaccine Doses Administered”, Our World in Data.

- 22. Lawk Ghafuri, “Iraqi Government Submits 2020 Budget to Parliament, Nine Months Late”, Rudaw, 14 September 2020.

- 23. Mansoor, “Iraqi Parliament Approves 2021 Budget”, The Siasat Daily, 1 April 2021.

- 24. Abbas Kadhim, “Rebuilding Iraq: Prospects and Challenges”, The Cairo Review of Global Affairs, Summer 2019.

- 25. Sinan Mahmoud, “Iraqi Prime Minister Blames Security Failures for ISIS Attacks”, The National News, 6 September 2021.

- 26. Mina Aldroubi, “ISIS Cannot Recover in Iraq Unless Government Loses Stability, Experts Say”, The National News, 10 September 2021.

- 27. Gregory Aftandilian, “The Realities and Challenges of a New US SOFA with Iraq”, Arab Center Washington DC, 15 August 2017.

- 28. “Non-interference Key to Iran-Iraq Relations, Says Kadhimi on Tehran Visit”, The National News, 22 July 2020.

- 29. “PMU Chief Reiterates Expulsion of US Forces from Iraq”, International Quran News Agency, 18 January 2021.

- 30. “Baghdad Rejects Iraqi Kurdish Forum’s Push for Normalization with Israel”, The Times of Israel, 25 September 2021.

- 31. Jane Arraf, “Talk of Iraq Recognizing Israel Prompts Threats of Arrest or Death”, The New York Times, 29 September 2021.

- 32. Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, “Are More Gulf States About to Normalize Ties With Israel?”, World Politics Review, 14 October 2020.

- 33. “Turkey Says Operation Against PKK in Iraq to Continue”, Al Jazeera, 13 August 2020.

- 34. “Iraq Condemns Turkish Strikes against PKK in Kurdistan Region”, Al-Monitor, 16 April 2020.

- 35. No. 34.