Rising Anti-Government Protests in Southeast Asia

- October 08, 2025 |

- IDSA Comments

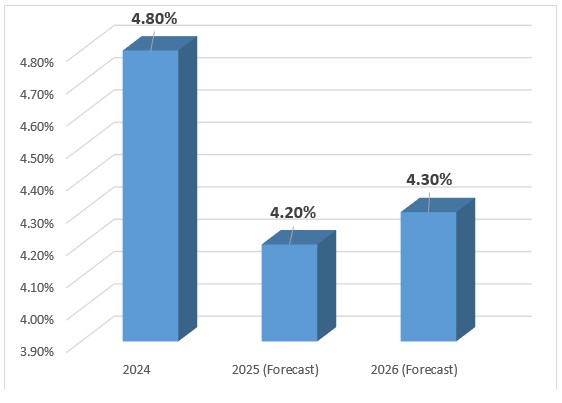

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) indicates that Southeast Asia’s GDP will decline from 4.8 per cent in 2024 to 4.2 per cent in 2025 and improve marginally to 4.3 per cent in 2026. According to the ADB’s Asian Development Outlook, the economic forecasts for Southeast Asia have been downgraded for 2025 and 2026 due to the continuing global growth slowdown and increased trade uncertainty. The weak external conditions have hurt business and consumer sentiments and threaten to disrupt investment in the region.[2]

The internal discord prevailing within Southeast Asia, along with external factors, impacts the existing socio-economic inequalities and the larger political environment. The economic slowdown across Southeast Asia in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008 affected the region’s socio-economic security. Further, the economic fallout due to the COVID-19 pandemic has fuelled the socio-economic divide within the region.

China’s growing assertiveness in the South China Sea has led to rising geopolitical tensions. The weak economic outlook for Southeast Asia could become more challenging amidst the ongoing geopolitical tensions, thereby accelerating protests and unrest in the region. Rising regional instability could further disrupt economic growth that is yet to reach the pre-pandemic level.[3]

The ‘People Power movement’ in the Philippines in 1986, which ended Marcos’s 20-year rule, was hailed as an example of peaceful revolution, which led to the restoration of democracy. This was followed by broader democratic trends across Southeast Asia, which included the 1991 Paris Comprehensive Peace Settlement, which ended Cambodia’s civil war, the landmark 1997 Constitution in Thailand and the adoption of reformasi (democratic reform process) by Indonesia from 1998.[4]

Current protests and demonstrations in Southeast Asia hinge on economic and poor governance issues. Given the ousting of governments in Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and, more recently, Nepal, the growing discontent in Southeast Asia in similar matters impacts domestic political stability. In Indonesia alone, more than 200 large demonstrations have taken place throughout 2025. The demonstration in Indonesia, which began in early 2025, escalated to violent mass protests by August with attacks against official buildings and public infrastructure across many cities.

The 28 August 2025 protests were intended to voice discontent about a proposed new housing allowance for Indonesian lawmakers totalling 50 million rupiah per month (US$ 3,057). The amount is equivalent to nearly 10 times the minimum wage. Further, the legislators also receive 12 million rupiah for food and 7 million rupiah for transport, on top of a base salary of 6.5 million rupiah. By contrast, Indonesia’s average monthly income is just 3.1 million rupiah.[5]

According to the 2025 State of Southeast Asia survey, Indonesia’s unemployment and economic recession, at 66.3 per cent, followed by widening socio-economic gaps and rising income inequality, at 61.1 per cent, were the top two concerns. The deteriorating economic environment since 2024, characterised by slowing economic activity, rising factory layoffs, and widened income inequalities, led to discontentment, especially among youth.

Further, since the start of Prabowo’s presidency in October 2024, the rupiah has depreciated by 7.5 per cent against the US dollar, giving rise to uncertainty about Indonesia’s future growth trajectory.[6] Social media and sophisticated digital technology have become powerful tools for mobilising protests globally, and they are a significant challenge for governments. During the difficult economic situation and anger against the government, Indonesian protesters have used online hashtags such as #SEAblings. Social media enabled solidarity and reciprocating support to be built in Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Brunei Darussalam and Thailand, which saw parallels with their own struggle against systemic injustices.[7]

The protests in Indonesia for better government accountability found solidarity in the Philippines, which is grappling with inequality and corruption. In the Philippines, on 21 September, widespread protests were held against corruption in the flood-control projects. Hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets to condemn corruption in government, even in provinces such as Baguio City, Iloilo City and Cebu City, where protests are not common.[8] Since July 2025, the Philippines has witnessed a series of typhoons and the southwest monsoon, bringing torrential rainfall that caused major floods across the country. A Congressional enquiry into the flood-control projects revealed million-dollar unfinished projects, some of which involve members of Congress. As per the Marcos Jr Administration, the alleged corruption could reach trillions of pesos.[9]

Flood-control projects are critical for the Philippines, given that typhoons and floods have the potential to cause significant economic disruption. Mass protests have been common in the Philippines, which in the past led to the ouster of two Presidents, Marcos Sr and Joseph Estrada, in 2001. The recent mass protests, which call for transparency and accountability, could have significant political fallout.

Due to political uncertainty, the ongoing mass protests directed towards improving governance and the state of the economy in Southeast Asia have the potential to become a significant disruptor for foreign trade and investment. While the role of ASEAN in managing the internal affairs of the member states is limited due to its norm of non-interference, it could play a key role in addressing the economic challenges at the centre of the ongoing internal discord.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

[1] “State of Southeast Asia Survey 2025”, ASEAN Studies Centre, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 3 April 2025.

[2] “Asian Development Outlook July 2025”, Asian Development Bank, 2025.

[3] Syarifah Huswatun Miswar, “Less Moral Governance: The Ghost in ASEAN Leadership”, Modern Diplomacy, 16 September 2025.

[4] Sergio Bitar and Abraham F. Lowenthal (eds), Democratic Transitions: Conversations with World Leaders, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2015, pp. 2–3.

[5] Sebastian Strangio, “Indonesian Protesters Clash With Police during Demonstrations Over Parliamentary Perks”, The Diplomat, 29 August 2025.

[6] Raphael Cecchi, “Indonesia: Protests Maintain the Government Under Pressure to Improve Socioeconomic Conditions”, Credendo, 25 September 2025.

[7] Adhiraaj Anand, “#SEAblings: The New Southeast Asian Transnational Solidarity Campaign”, The Diplomat, 15 September 2025.

[8] Kurt Dela Pena, “Fighting Corruption Beyond Street Protests: What’s Next?”, INQUIRER.NET, 24 September 2025.

[9] Chad de Guzman, “Filipinos Call for ‘Radical Change’ in Mass Protests Over Flood Money Corruption”, TIME, 21 September 022025.