US Funding Cuts and the Future of Africa’s Public Health

- May 28, 2025 |

- Issue Brief

Summary

The Trump administration’s decisions regarding funding cuts and withdrawal from the World Health Organization pose a serious threat to decades of progress in global health, especially in Africa. India can play a transformative role in Africa’s public health sector by ensuring sustainable access to essential drugs and providing affordable digital health solutions.

In January 2025, United States (US) President Donald Trump signed an executive order initiating the country’s withdrawal from the World Health Organization (WHO), marking his second attempt to sever ties with the global health body after a failed effort in 2020.[1] This move was followed in March by a sweeping freeze on foreign aid, including an 80 per cent cut to USAID funding.[2] Together, these decisions have triggered alarm among global public health experts, policymakers and international leaders.

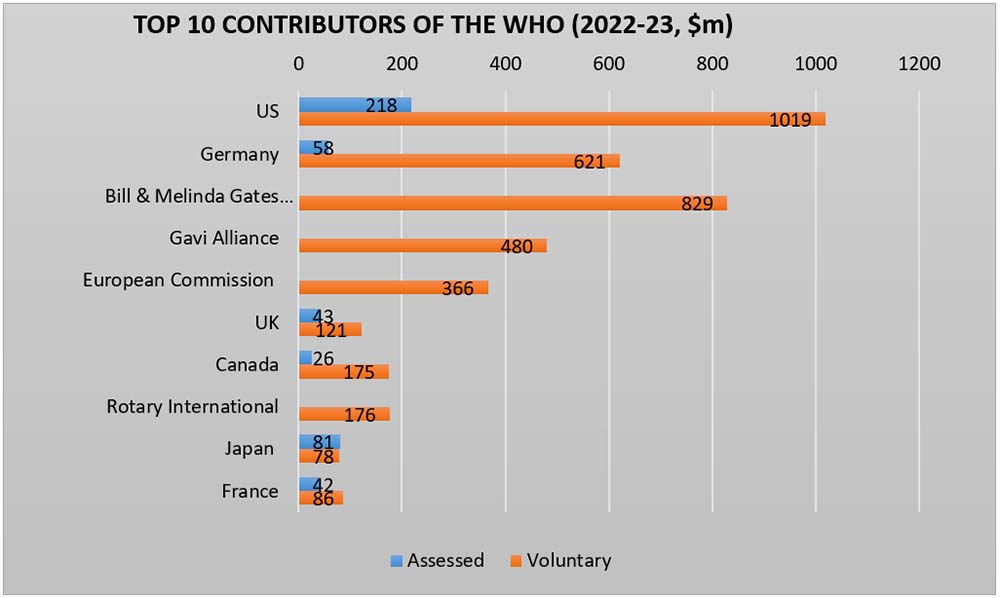

The US was the WHO’s largest contributor in the 2022–2023 budget cycle, providing 17 per cent of its total funding—US$ 1.284 billion of US$ 7.88 billion. This included 23 per cent of assessed contributions and 18 per cent of voluntary funding.[3] Likewise, USAID has played a critical role in strengthening global health systems by offering financial support, technical expertise and strategic guidance, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. In 2023 alone, USAID allocated US$ 20.6 billion to global health programmes, accounting for roughly 32 per cent of total international spending in the sector.[4]

These funding cuts pose a serious threat to decades of progress in global health, especially in Africa, where WHO and USAID-supported initiatives have been essential in combating pandemics, infectious diseases and public health emergencies. US support has underpinned immunisation drives, enhanced diagnostics and treatment capacity, and improved disease surveillance across the continent. At a time when Africa’s health systems remain fragile in the wake of COVID-19 and are grappling with resurgent outbreaks like Mpox and Marburg, the withdrawal of US support undermines Africa’s health security. This Brief explores the impact of the US withdrawal from WHO and sharp cuts to USAID funding on Africa’s public health.

Public Health Challenges in Africa

Africa faces a complex array of public health challenges that stem from systemic vulnerabilities, socio-economic disparities and environmental pressures. According to WHO, over 100 health emergencies take place annually in the African region, posing a significant threat to public health and development.[5] Infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis and neglected tropical diseases remain endemic in many African countries, despite global efforts to curb their spread. For instance, Africa accounts for over 70 per cent of global HIV cases, with an estimated 26 million people in the region living with HIV in 2023.[6] Malaria remains a significant public health challenge, with Africa accounting 94 per cent (233 million) of global malaria cases and 95 per cent (580,000) of malaria-related deaths in 2023.[7]

Moreover, Sub-Saharan Africa has some of the highest rates of preventable neonatal and maternal deaths and infectious disease fatalities. In 2022, it had the world’s highest neonatal mortality rate (27 deaths per 1,000 live births) and accounted for 57 per cent (2.8 million) of global under-5 deaths, despite having only 30 per cent of global live births.[8] This region alone bears 25 per cent of the global tuberculosis burden.

Beyond persistent infectious diseases, Africa is increasingly burdened by recurring epidemics and emerging health crises. Since 1976, Africa has experienced over 15 Ebola outbreaks, resulting in more than 13,000 deaths, with the deadliest occurring between 2014 and 2016, claiming over 11,000 lives.[9] The recent Mpox and Marburg outbreaks further highlight these vulnerabilities. Since January 2022, about 45,700 Mpox cases were clinically diagnosed and laboratory-confirmed across 12 African countries, leading to nearly 1,500 deaths, with a case fatality rate of 3.3 per cent.[10] Since 2000, the continent has faced five Mpox outbreaks and 12 Marburg outbreaks.[11]

Compounding these challenges is the continent’s fragile healthcare infrastructure, characterised by shortages of medical personnel,[12] inadequate funding and fragmented supply chains.[13] These deficiencies severely limit access to diagnostics, treatments and preventive interventions such as vaccines. The situation is particularly dire in rural and conflict-affected areas, where healthcare facilities are often understaffed or non-existent, and populations face significant barriers to accessing medical care.[14] Furthermore, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes, hypertension and cancer are rising rapidly across the region.[15] Historically, African health systems were not designed to address infectious disease outbreaks, leaving them ill-equipped to manage the growing burden of NCDs alongside persistent communicable diseases.

WHO in Africa

The WHO plays a pivotal role in addressing Africa’s public health challenges. Operating across 47 member states, WHO African Region (AFRO) focuses on disease prevention, health system strengthening, and emergency response, often in partnership with governments, NGOs, and institutions like the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC). WHO’s key initiatives include the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI), Universal Health Coverage, the Health Emergencies Programme, and campaigns against malaria, HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis.

With WHO’s support, the African region has made significant strides in healthcare over the past seven and a half decades. Some of WHO’s major achievements in the region include polio eradication efforts and HIV control. For instance, between 2010 and 2023, new HIV infections in the Eastern and South African region declined by 59 per cent, while HIV-related deaths fell by 57 per cent.[16] Similarly, since 2000, the maternal mortality rate has dropped by approximately 38 per cent.

WHO has played a vital role in tackling polio and malaria in Africa. In 2020, the African region was certified polio-free, with WHO helping to avert 9,00,000 polio-related deaths and prevent disability in 19.4 million people. It also supported over 20 countries in administering more than 500 million doses of the novel oral polio type 2 (nOPV2) vaccine.[17] In the fight against malaria, WHO contributed to preventing 2.1 billion cases and 11.7 million deaths globally between 2000 and 2022, with Africa benefitting the most—82 per cent of cases and 94 per cent of deaths averted were in the WHO African Region.[18]

During crises such as the Ebola outbreaks in West Africa (2014–2016)[19] and the Democratic Republic of Congo (2018–2020), the WHO coordinated international responses, deploying experts, supplies and funding to contain outbreaks.[20] In recent years, the WHO has increasingly prioritised pandemic preparedness and health system resilience, particularly after COVID-19 exposed critical gaps in Africa’s healthcare infrastructure. The organisation supports the Africa Health Strategy (2022–2030), which aims to achieve universal health coverage (UHC) and localise vaccine production initiatives.

US and Africa’s Public Health

The United States has been a major contributor to healthcare in Africa. As the largest financial supporter of the WHO, the US contributed 17 per cent of the organisation’s total funding in 2022–2023, amounting to US$ 1.2 billion. Of this, US$ 263 million was allocated to WHO African Region, supporting health emergencies, access to quality healthcare, polio eradication and epidemic prevention.[21] This financial support has been crucial in strengthening public health systems and responding to health crises across the continent.

The US has also partnered with WHO to combat disease outbreaks in Africa, including Mpox and Marburg. In 2023–2024, Washington contributed over US$ 22 million to support the Mpox vaccine delivery and capacity building in six African nations.[22] Additionally, it collaborated with the WHO and African countries to respond to the Marburg virus outbreak through enhanced surveillance, contact tracing and public health communication.

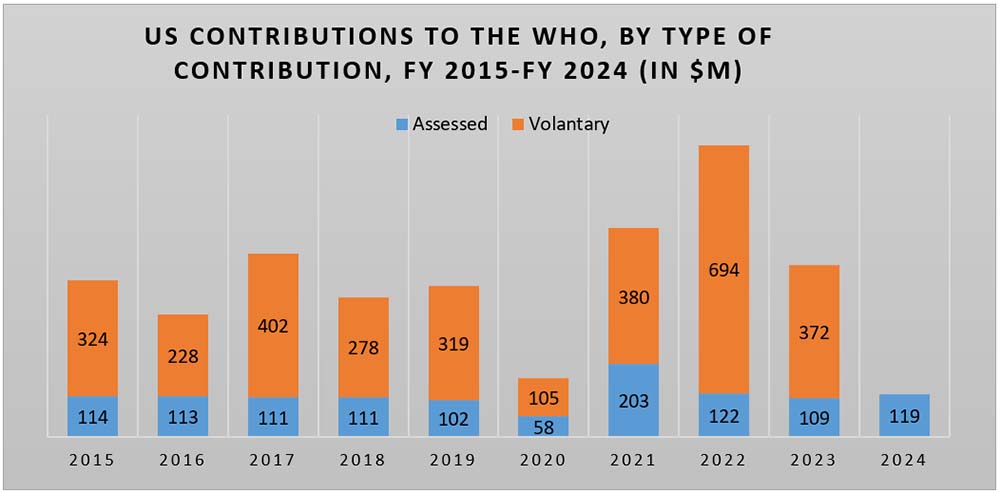

Figure 1. US Contributions to the WHO, by Type of Contribution, FY 2015–FY 2024 (in $m)

Source: “How WHO is Funded”, World Health Organization.

Figure 2. Top 10 Contributors of the WHO (2022–23, $m)

Source: “How WHO is Funded”, World Health Organization; “Contributors”, World Health Organization.

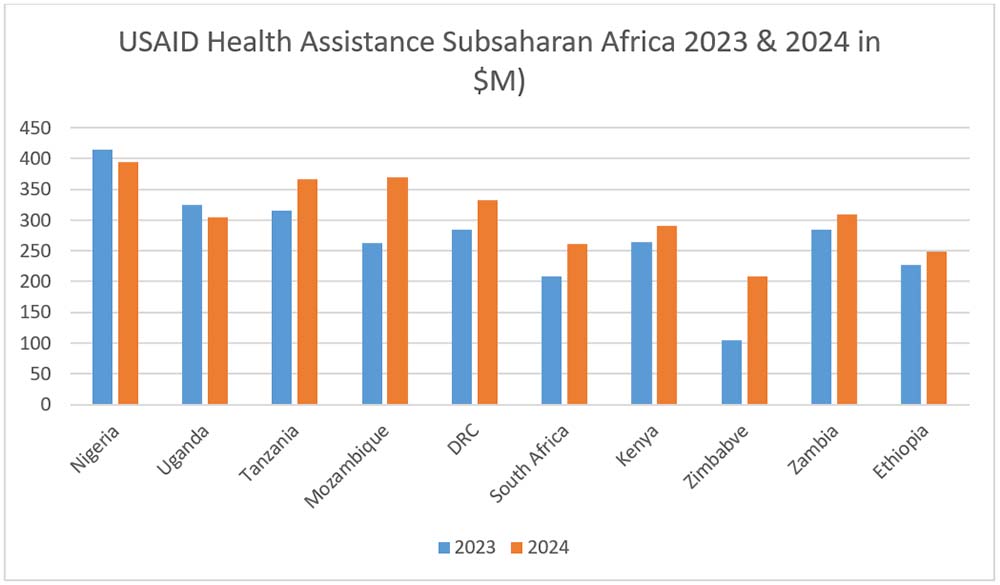

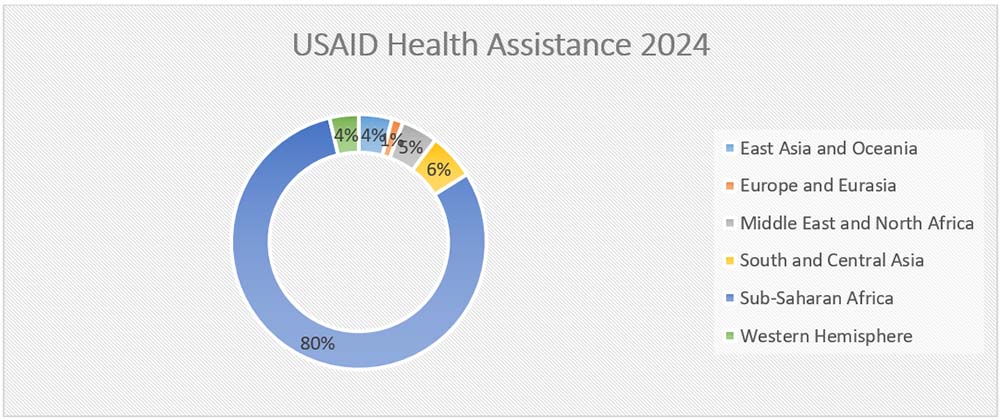

US development aid also plays a pivotal role in supporting national health programmes in African countries. In 2023, total US global health assistance stood at US$ 9.85 billion, with US$ 5.711 billion directed to Sub-Saharan Africa. Of this, USAID contributed US$ 7.206 billion globally, including US$ 3.962 billion for health programmes in Sub-Saharan Africa.[23] In 2024, US global health assistance increased to US$ 11.21 billion, of which US$ 5.08 billion was allocated to Sub-Saharan Africa. USAID’s share in 2024 rose to US$ 9.791 billion globally, with US$ 4.69 billion focused on health initiatives in Sub-Saharan Africa.[24]

Figure 3. USAID Health Assistance Sub-Saharan Africa 2023 & 2024 (in $m)

Source: https://foreignassistance.gov/

One of the most impactful US health initiatives is the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which has invested over US$ 120 billion in the global fight against HIV/AIDS since its launch in 2003.[25] PEPFAR supports over 3,40,000 health workers, a vital boost for Africa’s understaffed health systems. It also integrates HIV and TB care, and since 2019, has helped screen and treat women with HIV for cervical cancer in 12 high-burden African countries.[26] It is estimated that in the last two decades, PEPFAR has saved an estimated 26 million lives and continues to provide HIV prevention and treatment to millions.[27]

Figure 4. USAID Health Assistance 2024

Source: https://foreignassistance.gov/

Implications of US Funding Cuts on Africa’s Public Health

The withdrawal of US support from the WHO, along with significant cuts to USAID and PEPFAR funding, has had profound implications for public health systems across Africa. These reductions have jeopardized key components of healthcare infrastructure, weakened disease control mechanisms and diminished emergency response capabilities. As a result, access to vital services—including vaccines, antiretroviral therapy and essential medical supplies—has been severely disrupted, undermining efforts to control endemic diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis. Maternal and child health programmes are particularly at risk, raising serious concerns about potential increase in infant and maternal mortality rates.

The WHO plays a central role in disease surveillance and outbreak response for Ebola, cholera and COVID-19. With diminished US funding and technical support, these systems are weakening, delaying crisis responses and allowing diseases to spread. Vaccination campaigns coordinated by WHO and supported by US-funded initiatives like Gavi and COVAX face serious setbacks, placing millions of African children at risk of preventable diseases such as measles, polio and diphtheria.

Reduced funding has also placed a greater burden on African governments and regional organisations like the Africa CDC. With already limited healthcare budgets, many nations are struggling to fill the financial and logistical gaps left by the US pullback. This weakening of international cooperation compromises Africa’s ability to respond effectively to future pandemics.

The HIV response has been particularly hard-hit by the US approach. According to UNAIDS, US funding cuts have severely affected programmes in East and Southern Africa in four key areas—HIV prevention; treatment and prevention of vertical transmission; health facility operations; and community health systems. The DREAMS programme, which reached 2 million adolescent girls and young women in 10 countries, has been shut down. Prevention services for key populations have also been deprioritised.[28]

Fear and uncertainty about access to treatment are widespread. In South Africa, HIV testing among key populations dropped by up to 21 per cent in recent months, a decline attributed to reduced US support. PEPFAR, which once contributed over US$ 400 million annually and funded 15,000 health workers in South Africa alone, has significantly scaled back. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Haiti, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia, over half of HIV medications are procured through PEPFAR support.[29] There have already been reports of mothers and children in South Sudan dying after being unable to access a USAID clinic for life-saving HIV medication. In addition, over 80 per cent of the food kitchens supporting refugees from the Sudanese Civil War have been shut down.[30]

Countries like Kenya and Zimbabwe are facing critical service disruptions. In Kenya, staffing shortages have compromised HIV service delivery and patient privacy. Zimbabwe has seen setbacks in prenatal testing, early infant diagnosis and paediatric treatment. Across the region, thousands of health workers have been laid off, and untrained personnel are filling the void.[31]

In Kenya, 41,000 health workers have been affected; South Africa, 15,000; Mozambique, over 21,000; and Malawi, 4,451. Moreover, in Malawi, 20 per cent of electronic HIV data systems were down as of early 2025.[32]

Moreover, funding cuts are severely undermining HIV research efforts in Africa, leading to widespread clinic closures and disruptions in essential services. Thousands of health workers have been laid off, and untrained staff are being used to fill critical gaps. The impact extends beyond HIV, as neglected tropical diseases are also at risk of resurgence. The shutdown of US-funded programmes has disrupted drug donation and distribution systems across 26 countries, threatening to reverse years of progress in combating diseases that disproportionately affect the world’s poorest communities.[33]

India’s Potential Role

In the wake of the United States’ withdrawal from health aid programmes in Africa, including those under WHO, USAID and PEPFAR, critical gaps have emerged in the continent’s public health landscape. As previously discussed, Africa now faces several pressing challenges in its health sector. These include limited access to essential medicines, a shortage of trained healthcare professionals, weak pharmaceutical manufacturing infrastructure and high cost of medications.

India is uniquely positioned to fill this void and play a transformative role in Africa’s public health sector. As the world’s largest producer of generic medicines, India already supplies a significant portion of the essential drugs used in African health systems. India is one of the largest suppliers of pharmaceuticals to Africa, accounting for around 20 per cent of the continent’s imports and delivering medicines that are WHO-GMP certified and FDA-approved.[34] India’s pharmaceutical industry, known for high-quality, low-cost production, can help African countries maintain access to life-saving medications, particularly for diseases such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria.

Through expansion of direct government-to-government supply agreements and partnerships with African regional organisations, India can help ensure affordable and sustainable access to essential drugs. One of the major challenges India faces in expanding healthcare cooperation with Africa is the continent’s fragmented regulatory frameworks. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) offers a promising platform for harmonising standards across countries. Establishing Indian regulatory offices in Africa, and African counterparts in India, could further streamline drug approvals and improve access to affordable medicines.

India can also deepen its role in vaccine diplomacy across Africa. India accounts for 60 per cent of global vaccine production, making it the largest vaccine manufacturer in the world.[35] It is also one of the leading suppliers of low-cost vaccines, with approximately 65–70 per cent of the WHO vaccine requirements being sourced from India.[36] During the COVID-19 pandemic, India supplied millions of vaccine doses to African countries, reinforcing its credentials as a trusted partner in public health. India can support immunisation campaigns targeting diseases such as measles, human papillomavirus and cholera. Furthermore, collaborations with African vaccine manufacturers and research institutions can promote technology transfer and build long-term vaccine production capabilities on the continent. The India–Africa Health Sciences Collaborative Platform (IAHSP) can be expanded to strengthen these efforts.[37]

To address the shortage of trained healthcare professionals, India’s advances in telemedicine and digital health solutions can be effectively utilised. The Pan-African e-Network (PAeN) for telemedicine can be enhanced to tackle key challenges such as limited specialist access, poor digital infrastructure and the overall shortage of skilled personnel. Investing in satellite connectivity and solar-powered units can help overcome unreliable internet and electricity issues, enabling the programme’s expansion.[38] Additionally, real-time translation and culturally adapted communication can enhance patient interactions, while integrating PAeN with national health systems will ensure better coordination and continuity of care.

In short, by offering affordable health solutions, building local capacity and fostering sustainable partnerships, India can position itself as a reliable partner. These efforts align with India’s broader foreign policy vision of solidarity with the Global South and can be advanced through platforms such as the India–Africa Forum Summit, IBSA and BRICS. At a time when traditional donors are retreating from the continent, India has the opportunity to lead with purpose and principle.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

[1] “Withdrawing the United States from the World Health Organization”, Executive Order, The White House, 20 January 2025.

[2] “Rubio Announces that 83% of USAID Contracts will be Canceled”, NPR, 10 March 2025.

[3] “Funding by Contributors”, United States 2022–23, World Health Organization, 2024.

[4] “Congressional Budget Justification Foreign Operations Appendix 2”, Department of State, USA, 2025.

[5] “Emergencies”, WHO African Region.

[6] “HIV Statistics, Globally and by WHO Region”, World Health Organization, 22 July 2024.

[7] “Regional Data and Trends Briefing Kit”, World Health Organization, 11 December 2024.

[8] “New Born Mortality”, World Health Organization, 14 March 2024.

[9] “Ebola Virus Disease”, World Health Organization, 23 April 2023.

[10] Nicaise Ndembi et al., “Evolving Epidemiology of Mpox in Africa in 2024”, The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 392, No. 7, February 2025.

[11] “History of Marburg Outbreaks”, US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, 2 May 2024.

[12] “Chronic Staff Shortfalls Stifle Africa’s Health Systems: WHO Study”, WHO Africa Region, 22 June 2022.

[13] Chioma Stella Ejekam et al., “A Call to Action: Securing an Uninterrupted Supply of Africa’s Medical Products and Technologies Post COVID-19”, Journal of Public Health Policy, Vol.44, No. 2, 2023, pp. 276–284.

[14] Jean Kaseya, “Public Health Emergencies in War and Armed Conflicts in Africa: What is Expected from the Global Health Community”, BMJ Global Health, 2024.

[15] “Deaths from Noncommunicable Diseases on the Rise in Africa”, World Health Organization, 11 April 2022.

[16] “Eastern and Southern Africa: Regional Profile”, UNAIDS, 2024.

[17] “Celebrating 75 Years of Commitment to Public Health in Africa”, World Health Organization.

[18] “World Malaria Report”, World Health Organization, 30 November 2023.

[19] Adam Kamradt-Scott, “WHO’s to Blame? The World Health Organization and the 2014 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa”, Third World Quarterly, Vol. 37, No. 3, 2016, pp. 401–418.

[20] “WHO’s Response to the 2018–2019 Ebola Outbreak in North Kivu and Ituri, the Democratic Republic of the Congo”, World Health Organization, 3 October 2019.

[21] “United States of America: A Partner in Global Health”, World Health Organization, 23 December 2024.

[22] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] “The Future Role of The United States PEPFAR in Africa”, U.S. Department of State, 10 October 2024.

[26] “Pepfar Funding to Fight HIV/Aids has Saved 26 million Lives Since 2003: How Cutting It Will Hurt Africa”, The Conversation, 4 March 2025.

[27] “The US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)”, KFF, 13 May 2025.

[28] “Impact of US Funding Cuts on HIV Programmes in East and Southern Africa”, UNAIDS, 30 March 2025.

[29] “HIV Patient Testing Falls in South Africa After US Aid Cuts, Data Shows”, Reuters, 15 May 2025.

[30] “‘This Is Life and Death’: Trump’s USAID Shakeup Threatens Millions in Sudan”, Newsweek, 18 February 2025.

[31] “Impact of US Funding Cuts on HIV Programmes in East and Southern Africa”, UNAIDS, 30 March 2025.

[32] Ibid.

[33] “Crippling Tropical Diseases Threaten to Surge After U.S. Funding Cuts”, Science, 20 May 2025.

[34] “Pharmaceutical Exports from India”, IBEF, April 2025.

[35] “India’s Pharma Exports Grow Over 125% in Last 9 Years Investment of Rs. 21,861 Crore Received under PLI Schemes”, Press Information Bureau, Special Service and Features, Government of India, 13 June 2023.

[36] “Pharmaceutical Exports from India”, no. 34.

[37] “India Africa Health Science Platform”, Indian Council of Medical Research, 6 May 2025.

[38] “Satellite Connectivity The Key to Africa’s Digital Transformation?”, November 2023.