Source : Kremlin.ru, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

You are here

Relevance of Normandy Format Talks in the Ukrainian Crisis

Summary: Amidst the different dialogue channels aimed at defusing the Ukraine crisis, two discernible patterns are worth mentioning. One, where the major European leaders and the US President Joe Biden are talking bilaterally to Russian President Vladimir Putin, and two, where Germany and France have brought Ukraine and Russia on to the same table in an attempt to defuse tensions through talks among the four of them. The latter is known as the Normandy Format and receives special attention because it is the only format where the Ukrainian President is talking directly to his Russian counterpart. This issue brief analyses the relevance and efficacy of the Normandy Format talks in the ongoing East–West confrontation centring on Ukraine. It also analyses the reasons behind its lukewarm performance so far, and yet its inevitability in seeking a workable solution for the crisis by delving into the respective stakes and interests of the four major players.

Summary: Amidst the different dialogue channels aimed at defusing the Ukraine crisis, two discernible patterns are worth mentioning. One, where the major European leaders and the US President Joe Biden are talking bilaterally to Russian President Vladimir Putin, and two, where Germany and France have brought Ukraine and Russia on to the same table in an attempt to defuse tensions through talks among the four of them. The latter is known as the Normandy Format and receives special attention because it is the only format where the Ukrainian President is talking directly to his Russian counterpart. This issue brief analyses the relevance and efficacy of the Normandy Format talks in the ongoing East–West confrontation centring on Ukraine. It also analyses the reasons behind its lukewarm performance so far, and yet its inevitability in seeking a workable solution for the crisis by delving into the respective stakes and interests of the four major players.

The situation in Eastern Europe remains tense. The United States (US), in its first major move since the escalation, has reinforced the defence posture on NATO’s (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) eastern flank.1 Russia has accused the US and NATO of escalating tensions by deploying troops and weapons.2 This accusation has been rejected by the West citing Russia’s first move of deploying a hundred thousand troops along its border with Ukraine,3 and continuing joint military drills in Belarus4 and troop deployments in Moldova5 , which triggered the West to keep up its preparedness (Fig. 1).

Source: “US, NATO Send Written Response on Russia's Security Demands”, Deutsche Welle,

26 January 2022.

The above-mentioned commotion has a catch though. While NATO has taken a firm stand on defending its allies and significantly bolstering the trans-Atlantic security paradigm, it has refused to extend its collective security umbrella to defend Ukraine as the latter is not a NATO ally.6 Hence, the question about what would happen to Ukraine’s security remains to be tackled at the European level by a process that goes beyond the one endorsed by NATO. The role of energy politics, French and German business interests in Russia and vice versa that will be collaterally hit by further US sanctions,7 and the European Union (EU) lacking a potent defence arrangement are some factors that are forcing the Europeans to keep an open dialogue.

There are two ways to deal with a conflict without using military force—by deploying diplomatic measures and by imposing sanctions. Normandy Format is a diplomatic measure and its success lies in bringing the adversaries to the same table, not once but several times since the crisis broke out in Ukraine in 2014. French President Emmanuel Macron, who has been talking frequently to his Russian and Ukrainian counterparts, has repeatedly stressed on the diplomatic hand, the role of dialogue through the Normandy Format and the EU–Russia talks.8 Macron’s repeated appeals for diplomatic dialogue and emphasis on negotiation being the ‘only way’9 to defuse tensions also spring from fears around harsh sanctions which will jeopardise global financial systems especially those of Europe.10 However, in a situation where dialogue does not yield results, assessing the relevance of such talks supported by NATO members Germany and France, who are keen on going beyond the NATO for seeking workable solutions, becomes a key ponderable.

This issue brief analyses the relevance, scope and inevitability of the Normandy Format in the ongoing Russia–Ukraine tensions.

The Normandy Format

Normandy Format is a group of four countries—France, Germany, Ukraine and Russia—formed in the aftermath of the Crimea crisis in 2014 and is aimed at diffusing tensions between Russia and Ukraine. The representatives of the four countries met informally during the 2014 D-Day11 celebration in Normandy, France, to resolve the separatist war in the Donbass region of Ukraine, which was fuelled by Russia.12 The first meeting of the Normandy Format was initiated by the then French President François Hollande and German Chancellor Angela Merkel who brought Russian President Vladimir Putin and then Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko together for a dialogue.13 Despite setbacks, it continues to be an achievement of diplomacy as bringing arch-rivals and warring parties to the negotiating table is no less a feat under the shadow of a looming military conflict.

Its biggest claim to fame is the Minsk Protocol, a set of two agreements between Ukraine and Russia mediated by France and Germany in 2014 and 2015.14 In 2014, Normandy Format members established the Trilateral Contact Group (TCG), comprising Russia, Ukraine and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), for consultations to develop a peace plan. These talks led to the September 2014 Minsk Protocol (Minsk-I) and the February 2015 Memorandum and Package of Measures (Minsk-II), which together outlined conditions for the settlement of the conflict.15

Internal Setbacks to Normandy Talks

Certain roadblocks in the Minsk agreements have led to internal disagreements between Ukraine and Russia that have prevented the Normandy talks from achieving their full potential.

The Minsk-I Agreement: Minsk-I came at a crucial time when about 6,500 Russian troops invaded an ongoing war in Donetsk Oblast in September 2014 and Ukraine suffered heavy losses.16 Amidst heightened tensions, it was indeed a commendable feat to bring Ukraine and the Russian-backed separatists together in Minsk, in September 2014. Minsk-I was signed between representatives of Ukraine, the Russian Federation, and the separatists. It called for a ceasefire and several de-escalating steps.17 However, Minsk-I soon broke down and by January 2015, full-scale fighting had started again.18 In February 2015, a new ceasefire, known as Minsk-II, was negotiated.

Minsk-II Agreement: Brokered by Chancellor Merkel of Germany and President Hollande of France, Minsk-II produced a ‘package of measures for the implementation of the Minsk agreements’. This document, signed on 12 February 2015 by representatives from the OSCE, Russia, Ukraine and the separatists from Donetsk and Luhansk, has been the framework for subsequent attempts to end the war.19 The Minsk-II agreement was also endorsed by United Nations Security Council Resolution 2202 on 17 February 2015.20

Hasty drafting and contradictory provisions rendered the Minsk-II agreement ineffective,21 and Russia and Ukraine repeatedly accused each other of violating the terms of the agreement.22 The most glaring weakness of Minsk-II is that it does not make Russia a direct party. Although signed by the Russian Ambassador to Ukraine, Mikhail Zurabov, the agreement does not mention Russia—an omission that Russia has used to evade responsibility for implementation and maintain itself as a disinterested arbiter.23 Hence, in effect, it is only dealing with Ukraine and the separatists in the East thereby giving Russia the leeway to violate it citing technicalities.24

Source: Roman Goncharenko, “Ukraine Separatist 'Little Russia' Sparks Concern Over Peace Deal”, Deutsche Welle, 18 July 2017.

A few more Normandy Format meetings took place in the years that followed. The one held in October 2015 in Paris failed to draw the world’s attention, which was focused on Russia’s ongoing combat operations in Syria. Nevertheless, an agreement was reached to remove light and heavy weaponry. The meeting was dedicated to generating a timetable for elections in the Donbass region of Ukraine.25 France and Germany upheld support for elections under Ukrainian law and according to international and OSCE standards. However, President Putin allegedly used his influence over the separatists in getting the elections postponed, 26 yet again fuelling the already high level of distrust over Russian intentions. Analysts have argued that the cancellation of elections planned in October 2015 underscored that Moscow does indeed control the separatists.27

The Normandy Format talks happened again in Berlin in May 2016, but could not achieve any breakthrough. The next significant meeting of the Normandy Four happened in Paris in December 2019.28 The talks seemed promising in the beginning as an action plan to jump-start the stagnant peace process was signed, but deeply entrenched disagreements emerged soon. The action plan was dismissed a couple of hours after the meeting, with Russia accusing Ukraine of breaking the truce.29

The Steinmeier Formula: The Steinmeier Formula was articulated (though not published) in 2015 and 2016 by German Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier.30 It was designed to implement the political clauses of the Minsk accords (I and II), especially about holding elections in Donbass. It failed because it was in line with Russia’s interpretation but against Ukraine’s national interests. The Ukrainian President Zelenskyy backed down due to sharp reactions in Ukraine soon after signing its first written version in February 2019.31

The first Normandy Format talks this year were held on 26 January 2022 in Paris and were attended by advisers to the leaders of the Normandy Four.32 After eight hours of negotiations, a joint communiqué was released that stressed on reducing current differences in order to advance the negotiation process. Despite other disagreements,33 the advisers promised unconditional support to the observance of the ceasefire, which was agreed on 22 July 2020.34 An agreement was also reached on the next meeting in two weeks in Berlin.

The next Normandy Format talks that happened on 10 February 2022 saw nine hours of marathon negotiations. However, it failed to provide a breakthrough yet again. Though consensus was achieved on the Ukrainian suggestion to unblock the work of the Trilateral Contact Group towards a peaceful settlement about humanitarian issues in the Donbass war.35 All parties, including Moscow,36 reaffirmed their willingness to continue negotiations in the Normandy Format.37

There is, indeed, no linear solution to the crisis in Eastern Ukraine. In Moscow’s perspective, Ukraine remains an accident of history38 —unstable and internally split, more a geopolitical theatre of war and less a sovereign country. It seems evident in the comment made on Ukraine by Vladislav Surkov, ex-adviser to Putin, in a February 2020 interview in which he said: “There is no Ukraine. There is Ukrainian-ness. That is, a specific brain disorder.”39

Such fundamental disagreements between Ukraine and Russia on the Minsk I and II provisions are the biggest roadblock in achieving any resolution with the Normandy Format talks. Apart from these internal factors, Format has not been able to deliver because of certain external factors.

External Setbacks to Normandy Talks

Angela Merkel’s Exit: One of the consensus builders behind the Normandy Format, Angela Merkel, is no longer in office. She could speak Russian and was known for her impressive consensus-building skills.40 While the Normandy talks are not an individual-driven process, yet the long impact of the Merkel era and her equation with Putin is something that the newly elected Scholz cabinet does not enjoy.

A Lacklustre EU: The EU has become almost irrelevant in the East–West confrontation around the Ukraine crisis.41 For a long time, the EU believed in the idea that its economic weight may be converted into geopolitical power and influence.42 However, this idea did not work. Before the geopolitical aspirations of the EU are taken seriously, the EU needs to respond to economic coercion by China43 and structural changes within its security and fiscal policies as proposed by Macron. This is a serious concern for the EU as the question of Ukraine is a matter of stability in Europe. While the standoff has highlighted the EU’s precarious role so far, it has also provided them with an opportunity to maximise efforts for strategic negotiations and dialogue.44

US Not Being a Party: Ukraine has supported the US involvement in the Normandy Format for balancing Russia’s presence,45 because neither France nor Germany are in a position to deter Russia. The larger context of this crisis is hinging from NATO’s eastward expansion against which Russia wants legal guarantees that the US and NATO have been refusing.46 Despite speculations, the US has decided to not join the Format but continues to support its diplomatic developments.47 Russia has recently disapproved of US Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s call for revising the terms for the implementation of the Minsk agreements. From the Russian perspective, the US demand would make the entire peace process collapse.48 Without these developments, there would be little interest in the US to formally support the provisions of the Minsk agreements by joining the Normandy talks.

German and French Support to Normandy Talks

Despite the internal and external setbacks listed above, the Normandy Format talks are considered inevitable to German and French economic and strategic interests in Russia.

German Economic Interests in Russia: The new Chancellor of Germany, Olaf Scholz, has backed the Format and emphasised its effectiveness upon taking office.49 Germany’s vital economic interest lies in managing the conflict without letting violence escalate. It has been pushing for dialogue because of its dependence on Russia for natural gas and other commercial interests.50 Lobbying by corporate leaders has factored in the cautious approach adopted by Scholz since the start of the crisis.51 The leaders of some of Germany’s biggest companies like Siemens AG, Bayer AG, Deutsche Bank AG, SAP AG and Volkswagen AG are set to meet Russian President Putin early next month in a show of economic diplomacy aimed at urging all sides in the Ukraine standoff to back away from war.52 Last year, Germany’s exports to Russia grew by 15 per cent and its imports from Russia grew by 48 per cent from 2020.53 The latest sanctions that the US is planning to impose on Russia would also affect Germany.54 Germany is mindful of these collateral damages and is therefore trying its best to stick to mediation and dialogue.

Recently, Germany blocked the fellow NATO ally, Estonia, from providing military support to Ukraine and refused to issue permits for German-origin weapons to be exported to Kyiv.55

The German approach to Russia is far more accommodative than the stand taken by several other European members like the United Kingdom 56 , Poland, and the Baltic States57 and even by non-NATO members like Sweden58 and Finland.59

French Economic and Strategic Interests in Russia: As the clouds of a potential conflict loom large, Macron has been pushing for dialogue bilaterally, through EU–Russia talks and the Normandy Format.60 His approach is reminiscent of France trying to carve its own path in the post-World War II times, but more importantly it is part of Macron’s domestic political strategy amid campaigning for the presidential election due in April.61 French foreign policy, like Germany’s, favours cooperation and engagement with Russia rather than confrontation, also because French business interest has big stakes in Russia in the energy, locomotive and food sectors.62 Ever since Macron came to power in 2017, he has been engaging Putin, receiving him at the Palace of Versailles63 and his summer retreat in Bregancon64 with much fanfare, seeking a reset of relations with Moscow.

Russia’s favourable view of France may be inferred from Macron’s emphasis on the idea of European Defence that is separate from NATO.65 It is logical for Moscow to leverage this French anger towards the US through the recent unpleasantries around AUKUS.66 With AUKUS came the first serious cleavage in the 150-year-old US–France alliance.67 Moscow is well aware of these undercurrents and would reasonably try to take advantage of the situation by helping France undermine the importance of a US-led NATO in order to decrease Europe’s security dependence on it.68 In a classic zero-sum equation, diminishing NATO’s influence in Europe would be tantamount to a rise in Russia’s influence in the region. The Normandy Format not only helps with favourable optics for Putin respecting dialogue and negotiations but also Russia in engaging the two biggest powers of post-Brexit EU which are now obliged to keep their respective commercial interests and strategic aspirations safe.

Larger Economic Cost of the Crisis

The dialogue helps secure Russia’s larger economic interests too. Apart from Russian giant Gazprom’s stakes with Nord Stream 2, the volatility in financial markets due to ongoing East–West tensions is also worrying.69

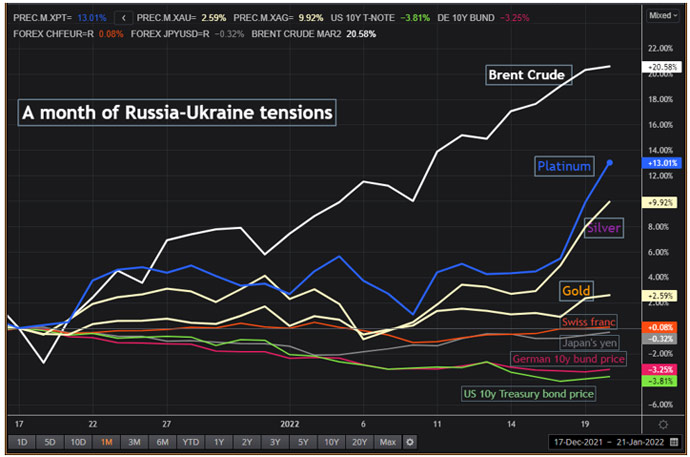

Russia has amassed huge foreign reserves due to the high prices of oil and gas. Energy analysts forecast that oil prices may be further pushed up from already-elevated levels of about US$ 90 a barrel to US$ 125, with gas prices following higher.70 Though it is not as advantageous as Russia would have wanted. The impact of rising gas prices has had a detrimental impact on the global economy (see Fig. 3 below).

Source: “How a Russian-Ukraine Conflict Might Hit Global Markets”, Reuters, 22 January 2022.

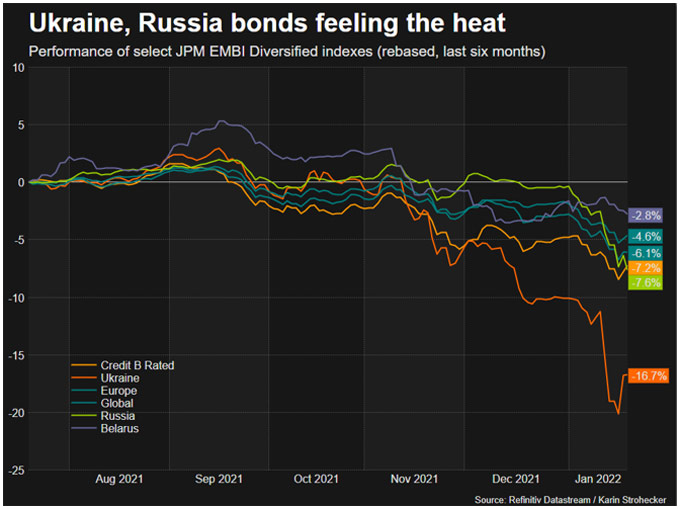

Russian and Ukrainian assets will be at the forefront of any markets fallout from potential military action. As shown in the figure above, both countries' dollar bonds have underperformed their peers in recent months as investors trimmed exposure amid escalating tensions between Washington and its allies and Moscow.71

Source: “How a Russian-Ukraine Conflict Might Hit Global Markets”, Reuters, 22 January 2022.

There has been heavy selling on Moscow’s volatile stock market, with the Molex index of Russian companies tumbling almost 6 per cent to its lowest level since December 2020, taking its losses in 2022 to almost 15 per cent. The rouble has hit a one-year low, dropping 2.5 per cent to more than 79 roubles to the US dollar.72 The Bank of Russia has announced halting the purchase of foreign currency in an attempt to ease pressure on the rouble.73 The Russian side is under mounting economic pressure. Although with China’s support,74 the efficacy of any more sanctions is a complicated matter in its own right75 , nevertheless, it will be unreasonable for Putin to invite more economic sanctions. Despite misgivings, the Normandy Format talks remain a rational choice for Russia as well.

Conclusion

Considering the nature of the Russia–Ukraine conflict, the intransigence of Ukraine’s and Russia’s positions, a sidelined and divided EU and the complexity of Russia's relations with different players in the West, the Normandy Format indeed offers a ‘Pareto optimal’ space76 for any sustainable solution towards settlement. Its efficiency should be assessed in terms of prevention of a ‘major war’ in Europe, development of settlement mechanisms like the Minsk agreements and the ceasefire line.77 The lasting solution to the Ukrainian crisis seems vague and impossible at the moment. However, the credibility of the Normandy Format lies in repeatedly bringing warring parties together in search of rational outcomes. Its efficacy augments in conjunction with other diplomatic efforts like the NATO–Russia Council, the OSCE, and the US–Russia strategic talks.78 However, its uniqueness lies in being the only platform that brings Ukraine and Russia together along with the two biggest powers of post-Brexit Europe. Therefore, it plays a cardinal role in deciding the course of the larger conundrum of NATO’s eastward expansion and Russia’s pushback against it.

The Ukrainian crisis is less about Ukraine, its national politics and foreign policy, and more about redefining the rules not only of the European security but also the international order and the simmering rivalry between great powers in particular. The space for dialogue and negotiations is, however, likely to remain open amidst all uncertainty.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. Mark Moore, “US Troops Depart Fort Bragg for Europe to Bolster NATO Forces During Ukraine Crisis”, New York Post, 3 February 2022.

- 2. Paul Sonne, Steve Hendrix and Rachel Pannett, “Kremlin Blasts U.S. for Deploying Troops to NATO’s Eastern Flank”, The Washington Post, 3 February 2022.

- 3. Andrew Roth, David Blood and Niels de Hoog, “Russia-Ukraine Crisis: Where Are Putin’s Troops And What Are His Options?”, The Guardian, 17 December 2021.

- 4. Holly Bancroft, “Russia Boosts Military Deployment to Belarus Ahead of Joint Drills”, The Independent, 3 February 2022.

- 5. “Russia Stages Drills in Moldova’s Breakaway Transnistria”, The Moscow Times, 1 February 2022.

- 6. John Haltiwanger and Ryan Pickrell, “The US Says it Won't Fight For Ukraine if Putin Invades, But It Could Still Get Pulled into a Conflict with Russia”, The Business Insider, 26 January 2022.

- 7. Alistair MacDonald, “US, EU Sanctions on Russia Could Ensnarl Western Oil Companies”, Mint, 30 January 2022.

- 8. Daniel Boffey and Angelique Chrisafis, “Macron Says EU Must Start Own Dialogue With Russia Over Ukraine”, The Guardian, 19 January 2022.

- 9. Jérôme Rivet, “EU leaders Vow Unity as Macron Sees Path on Easing Russia Tensions”, Philstar Global, 9 February 2022.

- 10. “US Sanctions Against Russia May Destabilize Global Financial System”, Tass, 30 January 2022.

- 11. Patrick Wintour, “Ukraine Tensions: What is the Normandy Format and Has It Achieved Anything?”, The Guardian, 26 January 2022.

- 12. Daniel Smith, “Russia-Ukraine Explained: What is Driving Russia's Efforts to Take the Country?”, Cambridge News, 10 February 2022.

- 13. “What is the ′Normandy format′ for Resolving the Crisis in Ukraine?”, Deutsche Welle, 26 January 2022.

- 14. Simond de Galbert, “The Impact of the Normandy Format on the Conflict in Ukraine: Four Leaders, Three Cease-fires, and Two Summits”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 23 October 2015.

- 15. Andrew Lohsen and Pierre Morcos, “Understanding the Normandy Format and Its Relation to the Current Standoff with Russia”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 9 February 2022.

- 16. Duncan Allan, “The Minsk-2 Agreement”, Chatham House, 22 May 2020.

- 17. Deutsche Welle, no. 13.

- 18. Craig Turp-Balazs, “The Minsk Agreements”, Emerging Europe, 9 February 2022.

- 19. Duncan Allan, no. 16.

- 20. “Unanimously Adopting Resolution 2202 (2015), Security Council Calls on Parties to Implement Accords Aimed at Peaceful Settlement in Eastern Ukraine”, The United Nations Meeting Coverage and Press Release, 17 February 2015.

- 21. Duncan Allan, no. 16.

- 22. Naja Bentzen, “Ukraine and the Minsk II Agreement: On a Frozen Path to Peace?”, Briefing European Parliamentary Research Service, European Parliament, January 2016.

- 23. Ibid.

- 24. Yuri Zoria and Alya Shandra, “Everything You Wanted to Know About the Minsk Peace Deal, But Were Afraid to Ask”, Euromaidan Press.

- 25. “Ukraine Ceasefire Respected, But Peace Process Unlikely to Conclude by End of Year”, RT World, 2 October 2015.

- 26. “Pro-Russian Donbas Rebels Agree To Postpone Elections”, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 6 October 2015.

- 27. Simond de Galbert, “The Impact of the Normandy Format on the Conflict in Ukraine: Four Leaders, Three Cease-fires, and Two Summits”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 23 October 2015.

- 28. David Herszenhorn and Rym Momtaz, “Normandy Talks Land in Paris but Fail to Deliver Peace in Ukraine”, Politico, 10 December 2019.

- 29. Neil, “Zelensky and Macron Discussed the Fate of the Normandy Format”, Global Happenings, 3 February 2022.

- 30. Vladimir Socor, “Steinmeier’s Formula: Its Background and Development in the Normandy and Minsk Processes (Part One) - Jamestown”, The Jamestown Foundation, 24 September 2019.

- 31. Duncan Allan and Leo Mitra, “Zelenskyy Finds That There Are No Easy Solutions in Donbas”, Chatham House, 23 October 2019.

- 32. Colm Quinn, “Normandy Format Talks Resume in Bid to Ease Russia-Ukraine Tensions”, Foreign Policy, 26 January 2022.

- 33. “Advisors to Normandy Four Leaders Adopt Joint Communiqué on Results of Talks”, Ukrainian News, 27 January 2022.

- 34. Pavel Polityuk, “Deal Reached for East Ukraine Ceasefire from July 27”, Reuters, 23 July 2020.

- 35. “At Talks in Berlin, Ukrainian Side to Seek Unblocking Work of TCG to Advance Peace Process”, Interfax Ukraine, 10 February 2022.

- 36. “Normandy Format Talks in Berlin End Without Results, Kremlin Official Says”, Tass, 11 February 2022.

- 37. “Yermak Announces a New Meeting of Normandy Format Advisers”, Rubryka, 12 February 2022.

- 38. Duncan Allan, no. 16.

- 39. “Surkov: I am Interested in Acting Against Reality”, Aktualnye Kommentarii (Actual Comments), 26 February 2020.

- 40. “Normandy Format' Talks for Resolving the Crisis in Ukraine”, Frontline, 27 January 2022.

- 41. Hacı Mehmet Boyraz, “EU’s Weak Role in Russian-Ukrainian Crisis”, Seta Foundation, 25 December 2021.

- 42. Gideon Rachman, “China and Russia Test the Limits of EU Power”, Financial Times, 17 January 2022.

- 43. Ibid.

- 44. Sonya Diehn, “Ukraine Crisis: A Geopolitical Chance for the EU?”, Deutsche Welle, 13 January 2022.

- 45. Kanaryan Lyudmila, “Normandy–Ukraine Wants More Pressure on Russia”, Unian Information Agency, 7 May 2021.

- 46. “US, NATO Send Written Response on Russia′s Security Demands”, Deutsche Welle, 26 January 2022.

- 47. “Telephonic Press Briefing with Dr. Karen Donfried, Assistant Secretary of State, Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs”, US Department of State, 21 December 2021.

- 48. “US Wants Minsk Agreements to be Revised”, Tass, 9 February 2022.

- 49. “Next German Chancellor Scholz Believes Normandy Format Should Once Again Become Effective Tool”, Interfax-Ukraine, 7 December 2021.

- 50. Jamie Mcintyre, “Germany’s and Europe’s Dependence on Russian Gas Weak Link in NATO Effort to Show United Front, Deter Ukraine Invasion”, Washington Examiner, 26 January 2022.

- 51. William Boston, “With Big Russian Interests, German Firms Look to Putin for Ukraine De-Escalation”, Wall Street Journal, 9 February 2022.

- 52. Ibid.

- 53. “Germany Exports to Russia - January 2022 Data”, Trading Economics.

- 54. “The West is Planning These Russia Sanctions – But They Would Also Have Consequences for Germany”, The Limited Times, 11 February 2022.

- 55. “Germany Blocks Estonian Arms Exports to Ukraine”, Deutsche Welle, 21 January 2022.

- 56. Oliver Holmes, “Boris Johnson Says There is ‘Clear and Present Danger’ of Imminent Russian Campaign in Ukraine”, The Guardian, 1 February 2022.

- 57. “Germany Blocks Estonian Arms Exports to Ukraine”, Deutsche Welle, 21 January 2022.

- 58. “Sweden Deploys HIMARS and Troops on Gotland Island amid Russia Tensions”, Global Defence Corp, 19 January 2022.

- 59. Jason Horowitz, “Finland's President Knows Putin Well. And He Fears for Ukraine”, The New York Times, 13 February 2022.

- 60. Daniel Boffeyand Angelique Chrisafis, “Macron Says EU Must Start Own Dialogue With Russia Over Ukraine”, The Guardian, 19 January 2022.

- 61. “France's Macron Takes Own Path, Seeks Dialogue With Russia”, Marketwatch, 27 January 2022.

- 62. Anastasiya Shapochkina, “War at What Price? Russia, NATO Weigh Cost of Ukraine Showdown”, France 24, 26 January 2022.

- 63. Emily Tamkin, “Putin to Meet Macron in Versailles”, Foreign Policy, 22 May 2017.

- 64. Charles Bremner, “Emmanuel Macron to Bring Putin in From the Cold at Brégançon Retreat”, The Times, 19 August 2019.

- 65. Victor Bouemar, “EU Collective Defence: What Does France Want?”, Clingendael Spectator, 29 September 2021.

- 66. Nicky Harley, “What is Aukus and Why Are the French Angry?”, The National News, 18 September 2021.

- 67. James Carden, “How AUKUS May Damage NATO”, Counterpunch, 24 September 2021.

- 68. Ibid.

- 69. Michael Janda, “How Russia's Ukraine Conflict Could Reshape Economics and Markets Even if it Doesn't End in War”, ABC News, 19 January 2022.

- 70. Ibid.

- 71. “How a Russian-Ukraine Conflict Might Hit Global Markets”, Reuters, 22 January 2022.

- 72. “Global Stock Markets Dive as Fears of Ukraine Conflict Rattle Investors”, The Guardian, 24 January 2022.

- 73. Shaun Richards, “What is the Economic Situation in Russia?”, Investment Watch, 26 January 2022.

- 74. Gordon C. Chang, “China is Making Sanctions on Russia Irrelevant”, The Hill, 10 February 2022.

- 75. Paulina Smolinski, “Senate Negotiations on "Mother of All Sanctions" Bill Against Russia Continue as Deadlines Loom”, CBS News, 11 February 2022.

- 76. Pareto-optimality is a concept of efficiency used in the social sciences, including economics and political science, and is named after the Italian sociologist, Vilfredo Pareto. In a Pareto-optimal (or Pareto-efficient) state, there is no alternative state that would make some people better off without making anyone worse off.

- 77. Dmitry Suslov, “‘Normandy Four’: The Best Possible Format”, Valdai Club, 2 October 2015.

- 78. Andrew Lohson and Pierre Morcos, “Understanding the Normandy Format and Its Relation to the Current Standoff with Russia”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 9 February 2022.